What governments keep getting wrong about community grants

Posted on 10 Mar 2026

If you spend long enough around government grants programs, a pattern emerges.

Posted on 24 Sep 2024

By Kylie Cirak, not-for-profit grantwriter

I am one of the much-maligned, the often despised and disrespected. Accused of making a buck from hard-working community groups, rorting a system, profiting from charities. No, I’m not a scammer or a con artist, a charlatan, a fraud, not even an influencer! I am a professional grantwriter.

Wearing one of my other hats, I have also been a grantmaker. I once sat on the board of the Aussie Farmers Foundation, and I was formerly the executive officer of the Alcoa Foundation in Australia.

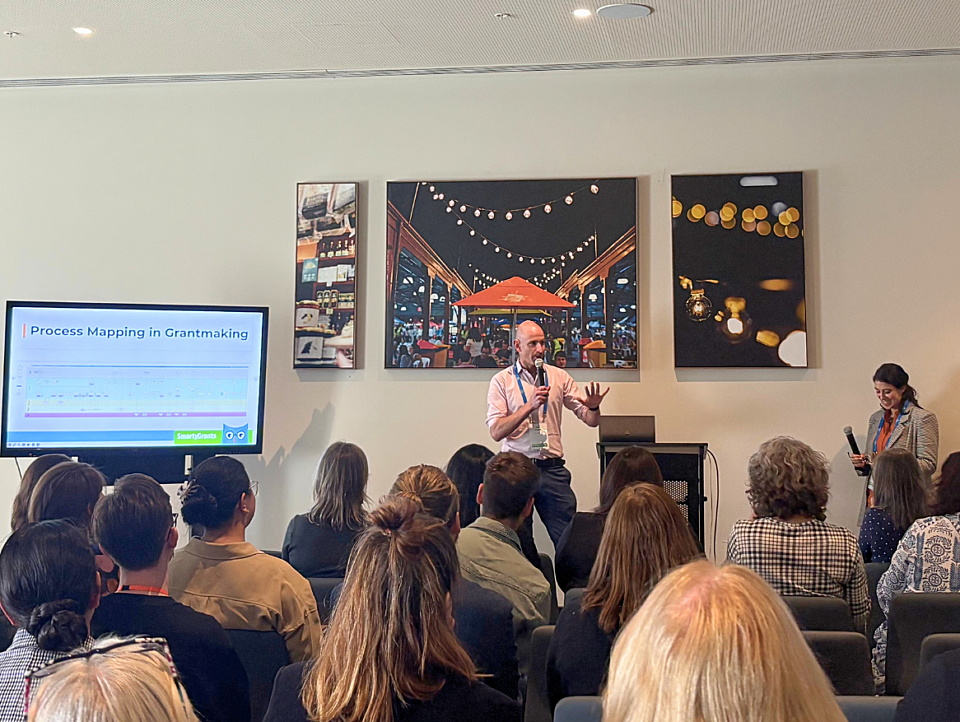

I have designed and taken part in processes which have administered millions of dollars. I occasionally help out my good friends at SmartyGrants reviewing new processes and tools. I know all about what grantmakers do, and why they must do it the way they do.

But I also understand why many grant applicants need the other Kylie, the grantwriter. Think of me – wearing my grantwriting hat – as an intermediary.

Consider me a helpful agent tasked with breaching the gap between a fabulous program or organisation needing funding, and your fabulous foundation or department with the needed funding.

I am the good fairy who translates the needs of the grant applicant into a language and format you understand.

And I use the word "translate" deliberately.

Grantmakers, you have your own language, policy you must adhere to, a grantmaking strategy. There is a whole micro-world within your organisation with its own culture. You're all over it because you live and breathe it every day in the workplace. You know the buzzwords, the buttons that must be pushed. You are absolutely across the difference between an outcome and an output because that is your job.

The grant applicant's job, by comparison, is caring for the dying, saving an endangered species, providing childcare, ministering to the drug afflicted, fighting for a cause. Grantwriting is not their core role. Writing anything may be outside their job description. They may be able to articulate what they do and why it is so important, but it will more often than not be overly emotive or written with their own internal jargon which is indecipherable to people outside their sector. It may be spoken from the heart, but without corresponding data, poorly written, and poorly conceived.

Is this because they don't care about getting funding? Is it a reflection of haphazard and unprofessional internal processes? Is it because they are slapdash and disrespectful to the grantmaking process? Because they didn't bother to read and re-read your carefully constructed guidelines written in your internal language by you to meet your internal needs? Maybe. But most of the time it is because they are time-poor, and grantwriting is – once again – not their core role.

Applicants are regularly punished for not understanding your language and your needs. They are also punished for not using proper grammar, for poor spelling, for badly constructed sentences. And don't tell me you look beyond this, because 90% of us don't – we can't help but judge the way people write, the way they speak, the way they present.

Grant applicants dearly want you to understand what it is they are doing and why it is so important that you support it, but they lack the skills to articulate it in the way that you want it.

And that's where a grantwriter can be an immense help to both the applicant organisation and the grantmaker.

We can act as translators. We have the time, the skill and the passion to sit and dissect your guidelines, your needs and your wants, and also the time and skill and passion to sit and listen to the applicant and their needs and wants. And we have the time, the skill and the passion to bridge that gap, to make sure the intent of the applicant has the right impact on you. We are translators and we put everyone on the same page.

"I am the good fairy who translates the needs of the grant applicant into a language and format you understand."

I know there are dodgy grantwriters who charge a bomb and add very little value. A couple of years ago I helped an organisation apply for a major government grant. They showed me a previous grant application they had written; they had also paid to have it reviewed and edited by a professional grantwriter. They were astonished and personally hurt that they had not got a look-in for that application. They blamed politics and personalities.

But I know exactly why they didn't get a look in. I am not exaggerating when I say the application, which had been professionally reviewed, was an abomination. I would have been ashamed to have submitted it. But they didn't know any different, because a "professional" had assisted them. I couldn't tell them that it was a horrible piece of work, because the person who had drafted it was so proud of it. So I lied and said we needed to do a complete rewrite so the funder didn't think we were just recycling.

So I know there are bad operators out there, in the same way that there are bad funders.

To give you an insight into how I roll when I am wearing my grantwriter hat, and perhaps reassure you that I am one of the good ones, I am going to share with you my cardinal rules for taking on a grantwriting gig.

These aren't necessarily the right rules or the best rules, but they are my rules.

It does my reputation no good if I take on a job that I know – even if it is just my gut telling me – has very little chance of success. I won’t take the job, even if a client is insistent. It leaves the applicant out of pocket and bitter, and it leaves me with my copy book blotted, with no repeat work from that client.

I work on an hourly-rate model. I state it up front. Some grantwriters work on a success fee, in which they take a cut of the grant if the application is successful. Some base their fee on a percentage of the grant "ask", regardless of success. I won't comment on or judge these models, but I will tell you why I like the model I use.

It is fair for everyone involved. It's not contingent on success but it's also not going to rip the guts out of a grant win. Years ago, I was working for a hospice, and in one month we worked out that if I had worked on a success fee, this hospice – with three paid staff and 58 volunteers, many of whom gave their time because they had lost a loved one and wanted to give back to the hospice – would have had to fork out $25,000 to me.

That would have been terrific for my bank balance, but terrible for them, because as we all know, many funders exclude costs associated with the development of the grant.

For some organisations, a success fee model works wonderfully. For many of the small not-for-profits I work for, it doesn't work at all. I won't tell you my rate for the same reason I won't ask you what you earn – it's neither of our business. But I will tell you my fee varies a bit, and what I charge a family violence organisation is very different from what I charge a corporate client.

That may sound like it's a rule to protect me, but it's a rule to protect everyone involved. Many organisations engage a grantwriter intending to pay them when they win the grant. As everyone knows, there is no guarantee that any application will be successful. It can leave a struggling organisation with a bill they cannot pay, and resentment that they must pay it. And yes, me out of pocket.

I don't have to explain that one!

When I start working with any organisation, I tell them that my main goal is that we work towards me being out of a job. This is clearly why I am not on Australia’s rich list.

We begin with a template which they fill out, which tells me all about who they are, and what they do, and why they are important and valuable. It has all the standard fields you might request of an applicant. I find out who has funded them, and for what, and whether the relationship is ongoing. It saves me time, and it saves them budget. Together we target funders and we start applying. We work together, and everything that is produced is saved, and the good stuff is added to that template, the master grant document. When we are unsuccessful we seek feedback, and we add that to the master grant document.

Anything of any use is added, and tweaked, and updated in our "living document". Because one day, maybe six years from when I start with them – or six weeks – they will look at that master document and say, "Everything we need is here. We don't need Kylie any more."

Does this mean I lose out? No. The majority of the time they recommend me to other organisations and the cycle begins again.

Very few of the 600,000-plus Australian community organisations can afford a permanent grantwriter. But I am tipping that the majority can afford me. And I am an investment. I make their lives easier, and trust me, I definitely make the lives of funding organisations easier too!

Kylie Cirak is the founder and director of Tiger Grace Consulting and a past director of leadership and diversity for the Institute of Community Directors Australia, an Our Community enterprise.

Posted on 10 Mar 2026

If you spend long enough around government grants programs, a pattern emerges.

Posted on 15 Dec 2025

A Queensland audit has made a string of critical findings about the handling of grants in a $330…

Posted on 15 Dec 2025

The federal government’s recent reforms to the Commonwealth procurement rules (CPRs) mark a pivotal…

Posted on 15 Dec 2025

With billions of dollars at stake – including vast sums being allocated by governments –grantmakers…

Posted on 15 Dec 2025

Nearly 100 grantmakers converged on Melbourne recently to address the big issues facing the…

Posted on 15 Dec 2025

The federal government is trialling longer-term contracts for not-for-profits that deliver…

Posted on 10 Dec 2025

A major new report says a cohesive, national, all-governments strategy is required to ensure better…

Posted on 10 Dec 2025

Just one-in-four not-for-profits feels financially sustainable, according to a new survey by the…

Posted on 10 Dec 2025

The Foundation for Rural & Regional Renewal (FRRR) has released a new free data tool to offer…

Posted on 08 Dec 2025

A pioneering welfare effort that helps solo mums into self-employment, a First Nations-led impact…

Posted on 24 Nov 2025

The deployment of third-party grant assessors can reduce the risks to funders of corruption,…

Posted on 21 Oct 2025

An artificial intelligence tool to help not-for-profits and charities craft stronger grant…